The largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found.

Press statement

The Staffordshire Hoard (wikipedia article) is an unparalleled treasure find dating from Anglo-Saxon times. Both the quality and quantity of this unique treasure are remarkable. The story of how it came to be left in the Staffordshire soil is likely to be more remarkable still.

The Hoard was first discovered in July 2009. The find is likely to spark decades of debate among archaeologists, historians and enthusiasts.

Leslie Webster, Former Keeper, Department of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum, has already said:

This is going to alter our perceptions of Anglo-Saxon England… as radically, if not more so, as the Sutton Hoo discoveries. Absolutely the equivalent of finding a new Lindisfarne Gospels or Book of Kells.

The Hoard

The Hoard comprises in excess 1,500 individual items. Most are gold, although some are silver. Many are decorated with precious stones. The quality of the craftsmanship displayed on many items is supreme, indicating possible royal ownership.

Stylistically most items appear to date from the seventh century, although there is already debate among experts about when the Hoard first entered the ground.

This was a period of great turmoil. England did not yet exist. A number of kingdoms with tribal loyalties vied with each other in a state of semi-perpetual warfare, with the balance of power constantly ebbing and flowing.

England was also split along religious lines. Christianity, introduced during the Roman occupation then driven to near extinction, was once again the principal religion across most of England

The exact spot where the Hoard lay hidden for a millennium and a half cannot yet be revealed. However we can say that it lay at the heart of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia. There is approximately 5 kg of gold and 1.3 kg of silver (Sutton Hoo had 1.66kg of gold).

The hoard was reported to Duncan Slarke, Finds Liaison Officer with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. With the assistance of the finder, the find-spot has been excavated by archaeologists from Staffordshire County Council, lead by Ian Wykes and Steven Dean, and a team from Birmingham Archaeology, project managed by Bob Burrows and funded by English Heritage. The hoard has been examined at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery by Dr Kevin Leahy, National Finds Adviser with the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

The Coroner for South Staffordshire, Andrew Haigh, is today (24th September 2009) holding an inquest on the find to decide whether it is treasure under the Treasure Act 1996. If it is declared treasure, the find becomes the property of the Crown, and museums will have the opportunity to acquire it after it has been valued by the Treasure Valuation Committee. The Committee’s remit is to value all treasure finds at their full market value and the finder and landowner will divide the reward between them. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent, and Staffordshire County Council wish to preserve the find for the West Midlands.

Sword hilt fittings

The Hoard is remarkable for the extraordinary quantity of pommel caps and hilt plates. There have been 84 pommel caps and 71 sword hilt collars so far identified. These highly decorated items would have adorned a sword or seax – a short sword/knife. Most are of gold and many are beautifully inlaid with garnets. Such elaborate and expensive decoration would have marked out the weapon as the property of the highest echelons of nobility. The discovery of a single sword fitting is a notable event: to find so many together is absolutely unprecedented.

Helmets

Parts from several highly decorated helmets are likely to be among the finds, although piecing these together is likely to take considerable time and effort. Among the most conspicuous is what appears to be a magnificently decorated cheek-piece decorated with a frieze of running, interlaced, animals. Interestingly, this piece has a relatively low gold content. This may be the result of being specially alloyed to make it more functional and able to withstand blows.

A beautiful figure of an animal is also possibly the crest of a helmet. Large numbers of fragments of “C” sectioned silver edging and reeded strips could also be helmet fittings. Similar fragments, made from base metal, formed part of the Sutton Hoo helmet, found in a rich grave in Suffolk, in 1939.

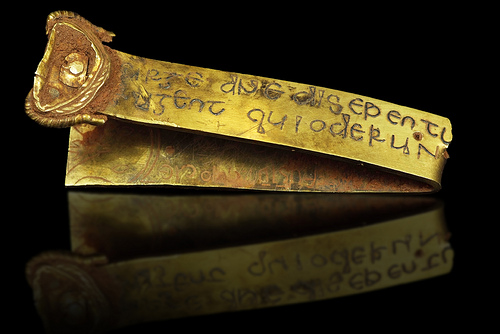

Biblical inscription

A strip of gold bearing a Biblical inscription in Latin is one of the most significant and controversial finds. Michelle Brown, Professor of Medieval Manuscript Studies, has suggested the style of lettering dates from the seventh or early eighth centuries. The relatively crude lettering may have been the work of someone more used to writing on wax tablets.

The suitably warlike inscription, mis-spelt in places, is probably from the Book of Numbers Ch. 10 v 35 and reads:

Surge domine et dissipentur inimici tui et fugiant qui oderunt te a facie tua ~ “Rise up, o Lord, and may thy enemies be dispersed and those who hate thee be driven from thy face”

The folded cross

The only items that are clearly non-martial are two, or possibly three, crosses. The largest may have been an altar or processional cross. Other than the loss of the settings used to decorate it (some of which are present but detached) it is intact. However it has been folded, possibly to make it fit into a small space prior to burial. This lack of apparent respect shown to this Christian symbol may point to the Hoard being buried by pagans, but Christians were also quite capable of despoiling each other’s shrines.